Great Barrier Reef bleaches again, as predicted, but continues exporting corals

The Coral Bleaching HotSpot prediction method, developed by the Global Coral Reef Alliance in the 1980s, has projected every major bleaching event in the Great Barrier Reef. We warned a new bleaching event was about to happen there about a month ago, and now field confirmation has come through.

Townsville Bulletin, Nov 27 1998

Townsville Bulletin, Nov 27 1998

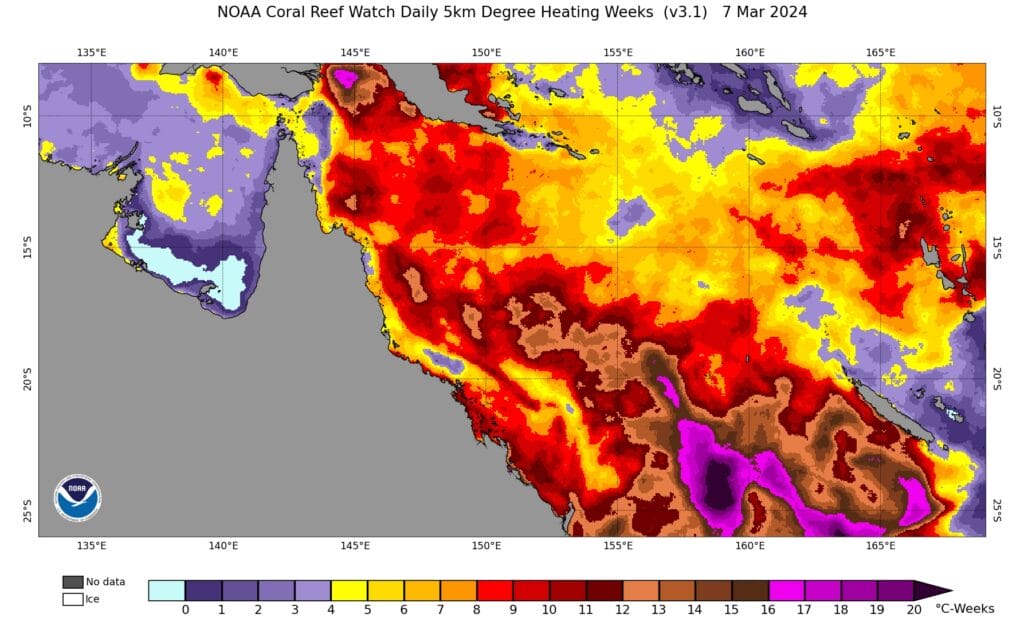

The intensity of bleaching depends on how long it stays excessively hot. The current product of excess heat and duration is shown below for the GBR. Areas in yellow will see most corals bleach, areas in red will see serious mortality of vulnerable species, areas in black will see near total mortality of even the most high temperature tolerant species.

What is truly shocking is that the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority continues to authorize the export of up to 200,000 kilograms of live coral per year!

Great Barrier Reef: New mass bleaching event hits World Heritage site

March 8 2024

By Tiffanie Turnbull,BBC News, Sydney

Climate Council

A recent photo of the bleaching damage on the Great Barrier Reef

Australia’s iconic Great Barrier Reef is suffering another mass bleaching event, officials have confirmed.

Bleaching occurs when heat-stressed corals expel the algae that gives them life and colour.

It is the fifth time in eight years widespread damage has been detected at the Unesco World Heritage site.

Only two mass bleaching events had been recorded until 2016, and scientists say urgent climate action is needed for the reef to survive.

“The frequency and scale at which these mass bleaching events are now occurring is frightening – every summer we’re holding our breath,” said Greenpeace Australia’s David Ritter.

“Claims that Australia is taking the health of the Great Barrier Reef seriously ring hollow when we continue to expand and subsidise the coal and gas industry to the tune of billions every year.”

“It’s literally cooking the Reef,” the Climate Council’s Simon Bradshaw added.

Stretching over 2,300km (1,400 miles) off Australia’s north-east coast, the Great Barrier Reef is the world’s largest coral system and one of its most biodiverse habitats.

An aerial survey of 320 reefs – from the tip of Australia to the city of Bundaberg – showed most are experiencing prevalent bleaching, after a summer of heightened sea temperatures.

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority said in-water examinations are underway to determine the severity and depth of the damage – which likely varies greatly across the reef.

The body’s Chief Scientist Roger Beeden told the BBC that bleaching in the southern zone though, was the worst in almost 20 years, and could become “unprecedented”.

“It’s too early to say what the full consequences of this event is,” he said. “If the conditions cool, we could see a lot of what’s bleached recover.”

Over the past decade the reef has rebuilt itself from other mass bleaching events, severe tropical cyclones, and crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks, he added.

Record-breaking global sea temperatures have recently triggered similar bleaching events in the northern hemisphere, and this week bleaching was also spotted on the world’s southern-most reef at Lord Howe Island – which too lies in Australian waters.

The Great Barrier Reef has been heritage-listed for over 40 years due to its “enormous” importance, but Unesco says the icon is under “serious threat” from warming seas and pollution.

Successive Australian governments have fought to keep the body from declaring the tourist drawcard “in danger”, which could see it lose heritage status. The decision will be reviewed again in July.

Calling climate change “the biggest threat to coral reefs worldwide”, Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek said her government has increased funding for reef conservation and introduced stronger emissions-reduction targets.

“It’s essential we do everything we can to protect this amazing place for our kids and grandkids,” she said.

The UN’s most recent climate change report found the prevalence of future mass bleaching events depends on how quickly the world cuts emissions.

Calls for change as tonnes of coral taken from Great Barrier Reef

Australia remains one of the world’s top exporters of corals despite experts urging countries to work towards limiting the trade to ‘the lowest level possible’.

Tracy Keeling

March 5 2024

The marine aquarium trade is booming, with research showing 55 million invertebrates and fish are sold globally every year. Corals feature prominently in the sector, thanks to hobbyists’ preferences for mini reef replicas.

Combined with their use in jewellery and curios, the aquarium trade has led to stony corals being the most heavily exploited marine animals in internationally regulated trade.

Australia is among the top exporters of corals, according to records from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which regulates global trade in the animals and many other wild species.

A better understanding of harvest levels in different species is required to protect the Great Barrier Reef, according to one expert. Source: Morgan Pratchett

The country’s largest fishery is in Queensland, where commercial collectors hand pick live stony corals, coral rock, soft corals, and sea anemones from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, outside of certain restricted zones. The maximum allowable commercial ‘catch’ in the Queensland Coral Fishery (QCF) is 200,000 kilograms annually – although the actual harvest is often less – with limits in place for different types of coral products and several species.

Is coral collecting sustainable?

Coral reefs worldwide face existential threats from climate change, plastic pollution and disease. Indeed, 2023 saw widespread bleaching in the Americas and scientists warn 2024 may prove even worse across the Indo-Pacific. Reef ecosystems can also be severely damaged by storms and other extreme weather events.

Given these threats, the coral trade is facing increased scrutiny, including extraction in the QCF.

With climate change, plastic pollution, and disease already affecting reefs, there are warnings to limit commercial extraction of wild corals. Source: Getty (File)

According to Morgan Pratchett, marine biology and aquaculture professor at James Cook University, coral collection on the Great Barrier Reef has long been presumed to be sustainable, due to the reef’s size and selective harvesting. But amid rising threats to reefs from other dangers, he says a good understanding of wild stocks’ status and their sensitivity to non-fishery threats is essential to determine whether harvesting is sustainable.

Presently, the necessary understanding about corals in the QCF is lacking, which is why Pratchett is involved in assessing potentially at-risk corals in this fishery. “This is the first step to ensuring that coral harvesting is sustainable,” he says.

Pratchett also suggests a better understanding of harvest levels in different species is necessary. This applies to the industry more broadly, as many corals are only identified at their genus level in trade records, due to species being difficult to distinguish. This makes exploitation levels unclear.

How coral farming could save reefs

Amid uncertainties over the coral trade’s impact, some countries, such as Indonesia, are now farming many internationally traded corals, although these operations often still rely on extraction from ‘donor colonies’ of corals in the wild.

Others like Belize don’t allow commercial exports of live stony corals. At a CITES meeting in 2023, its fisheries officer, Mauro Gongora, urged countries to work towards limiting the trade to “the lowest level possible,” due to corals’ importance and vulnerability.

Belize (pictured) no longer allows live stony corals to be commercially taken, however Australia is among the top exporters of corals. Source: Mauro Gongora

Reefs are home to around 25 per cent of all known marine life. According to the United Nations, the ecosystems are worth $US375 billion annually in terms of the resources and benefits they provide, meaning their destruction can threaten food security, jobs, and more, Gongora says.

He also emphasises that reef-building corals protect coastlines and people because reef structures provide a buffer from storms. For instance, the Great Barrier Reef limits incoming wave energy, thereby safeguarding coastal ecosystems and people, as The Conversation reported.

Globally, the extent of living corals on reefs has dropped in area by half since the 1950s, according to research. With the threats they face showing no sign of abating, Gongora warns, “if we are not very careful in terms of how we regulate the trade of corals, we can find ourselves in very big problems in the future.”

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.